11 Oct On This Day In History: 100th Anniversary of Fire Prevention Week Originated From the Great Chicago Fire of 1871

The Great Chicago Fire, which occurred over 48 hours on October 8-10, 1871, is considered one of the most famous fires in U.S. history. Urban legend has spurred the apocryphal claim that the fire was the result of a clumsy bovine kicking over a lantern inside the O’Leary family barn and starting the historic fire that killed an estimated 300 people, destroyed 17,500 structures, and left 100,000 people homeless. Another equally viable theory is that a group of men was gambling in the O’Leary barn and knocked over a lantern.

Either way, once the fire sparked in Patrick and Catherine O’Leary’s barn on Chicago’s southwest side, strong winds, a long summer drought, and a host of wooden structures were all factors in a runaway blaze that tore through the heart of Chicago burning more than 2,000 acres over two days. The weather on that Sunday, October 8 evening included dry conditions resulting from only one inch of rain falling since July 4 and gusts of southwest winds carrying embers into a city that was poorly prepared for the perfect storm of factors that fed the fire. Along with the city’s sidewalks, more than two-thirds of its buildings were made entirely of wood causing the fire to blaze ferociously, gobbling up everything in its path that spanned four miles long by one mile wide and continued to burn wildly throughout the following day.

Human error also played a role in the Great Chicago fire’s continued spread. In addition to firefighters initially being given wrong directions to the fire and losing precious time, they only had 17 horse-drawn steam pumpers for the entire city. A second snafu occurred when an alarm sent from the area near the fire failed to register at the courthouse where the fire watchmen were stationed.

Bad luck was also to blame. Firefighters were depending on the south branch of the Chicago River to act as a natural firebreak, however, the river’s banks were populated with lumber and coal yards, warehouses, barges, and numerous bridges that instead helped spur the fire to jump the river and continue on its destructive path. And although it had a slate roof, the Chicago Waterworks plant, which was the main source of water for the city’s woefully understaffed fire department, was constructed of pine and was quickly engulfed by flames bringing firefighting efforts to a standstill.

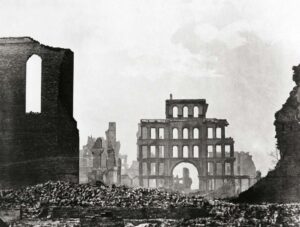

As firefighters looked on helplessly the fire burned until finally coming to heel late on October 9 when the weather gods took pity and released a rainstorm giving a much-needed boost to the Chicago Fire Department’s fire extinguishing efforts. The rain in combination with the fire running out of fuel to feed it left one-third of the city in a ruin of embers and ashes by Tuesday morning.

The city of Chicago quickly rebuilt implementing massive safety and code changes. The width of the city’s streets was made larger to act as a natural firebreak, according to Casey Grant of the National Fire Protection Association Fire (NFPA). Additionally, building codes were changed to include the use of fireproof construction materials such as brick, stone, marble, and limestone. “Code changes to building materials made the exterior of buildings much more fire resistant. In terms of design, we want to try to keep fires confined to the building of origin if a fire does occur and not spread from building to building as we have seen in some of these great fires of that era,” said Casey during a 2016 interview.

Another significant life safety contribution resulting from the 1871 Windy City tragedy was the establishment of Fire Prevention Week in 1922. Within a couple of years of the historic fire, Chicagoans began memorializing the city’s restoration and fire’s anniversary with festivities that several decades later would be dubbed Fire Prevention Week by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). As the longest-running public health observance in the U.S., this year Fire Prevention Week is celebrating a historic 100 years with a campaign message of “Fire won’t wait. Plan your escape.” to educate the public about simple but important actions they can take to keep themselves and those around them safe from home fires.

“Today’s homes burn faster than ever. You may have as little as two minutes (or even less time) to safely escape a home fire from the time the smoke alarm sounds. Your ability to get out of a home during a fire depends on an early warning from smoke alarms and planning,” said Lorraine Carli, vice president of Outreach and Advocacy at NFPA.

Senior Fire Protection Consultant Jorge Velasco, CET of national fire protection engineering firm TERPconsulting concurs, noting that it’s important to plan and practice home fire escape drills. “Everyone needs to be prepared in advance so that they know what to do when the smoke alarm sounds. Given that every home is different, every home fire escape plan will also be different,” explained Jorge. He advises families to “organize and practice a plan for everyone in the home. Children, older adults, and people with disabilities may need assistance to wake up and get out of the home in an emergency so be sure to arrange for someone to help them.”

As we acknowledge the 100th anniversary of Fire Prevention Week and the lessons learned from the Great Chicago Fire, there’s one final commemoration that resulted from the legendary blaze. In 1956, in ironic tribute to the famous fire, the Chicago Fire Academy was built on the site where the O’Leary family’s barn once stood. To this day, the school’s purpose is to train new firefighters.

No Comments