01 Dec On This Day In History: Remembering the Our Lady of the Angels School Fire on its 65th Anniversary

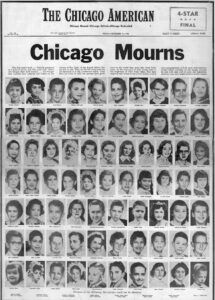

In 1958, a tragic incident unfolded at Our Lady of the Angels School in Chicago, Illinois, leading to three nuns and 92 children losing their lives in a devastating fire. The incident occurred shortly before the scheduled dismissal of classes on that first day of December. In a desperate attempt to escape the engulfing toxic smoke and flames, additional children sustained injuries by resorting to jumping out of second-floor windows.

Operated by the Archdiocese of Chicago, Our Lady of the Angels was an elementary and middle school comprising kindergarten through eighth-grade classes on Chicago’s West Side. The 1,600-student school was one of several buildings associated with the large Catholic parish. The fire was primarily confined to the second floor of the school’s north wing, where all the deceased occupied classrooms. The first floor of the north wing and the entire south wing were not involved in the fire aside from some minor smoke inhalation problems.

The fire originated in the basement of the two-story school near the foot of a stairway, with ignition starting in a cardboard trash barrel a few feet from the northeast stairwell. At the same time, superheated air and gases surged into an open pipe chase near the source of the fire. The pipe chase made an uninterrupted conduit up to the cockloft above the second-floor classrooms.

Both poor building design and lack of fire protection systems colluded to foment the deadly blaze. In addition, the school only had one fire escape, no automatic fire alarm, heat detectors, direct alarm connection to the local fire department, or industrial fire doors leading from the stairwells to the second-floor corridor.

The school did follow local fire codes in that its exterior was brick, which prevented the fire from spreading from building to building, as happened in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Yet its interior was problematic due to ubiquitous wood materials, including stairs, walls, floors, doors, roof, and cellulose fiber ceiling tiles. Consequently, the regular pathways of corridors and stairways became obstructed by smoke, heat, fire, and toxic gases, impeding the students’ typical means of escape.

Other high-risk fire issues included floors heavily coated with flammable petroleum-based waxes, the roof not being vented, and repeatedly sealed with tar paper. Fire investigators also found that fire doors only protected part of the second floor—and, regrettably, they were propped open to enable students to easily pass during the school day.

Four fire extinguishers were in the north wing; however, they were each mounted seven feet off the floor, out of reach for many adults and children. The sole fire escape was located at one end of the north wing. But reaching it necessitated traversing the main corridor, and unfortunately, it quickly filled with suffocating smoke and superheated gases.

Even though Our Lady of the Angels School had undergone a routine fire department safety inspection weeks before the tragedy, the school was exempt from legally adhering to all 1958 fire safety codes, thanks to a grandfather clause within the 1949 standards. “There are no new lessons to be learned from this fire; only old lessons that tragically went unheeded,” said Percy Bugbee, who was serving as the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) president then.

Following the blaze, the City Council of Chicago enacted ordinances to strengthen its fire code that included a law requiring a fire alarm box to be installed in front of schools and other public assembly venues. An additional stipulation that was enacted mandated the installation of sprinkler systems in schools where it was deemed essential. Corresponding amendments to the Illinois state fire code were also approved.

“The tragedy also led to massive overhauls of fire codes across the United States in approximately 16,500 older school buildings,” explains Kaitlin McGillvray, PE of national fire protection engineering firm TERPconsulting. “Such changes included the requirement of fire alarms, automatic sprinkler systems, exit doors opening outward, window egress heights, one-hour fire-resistance-rated walls, dedicated emergency lighting, separation of heating equipment, and self-closing fire doors at stairwells.”

Communities nationwide also increased the frequency of legally mandated fire drills throughout the academic year. “The tragedy emphasized the importance of regular fire drills and well-established evacuation plans in schools and public buildings,” said Kaitlin. “Subsequent regulations required schools and other institutions to conduct frequent fire drills to ensure occupants knew how to respond in case of a fire.”

Although significant fire safety progress was made because of the tragic blaze, the official determination of the fire’s cause remains unknown. In 1962, a boy who attended Our Lady of the Angels School during the blaze confessed to starting the fire. At the time, he was only 10 years old and a fifth-grade student. However, a family court judge later deemed the evidence inadequate to support the confession. Consequently, the official cause of the fire continues to be a mystery.

The fire’s impact has forever been emblazoned in pop culture courtesy of one of the most popular bands of the 1980s. Among the fire survivors was an eight-year-old third-grader named Jonathan Friga, who later gained fame as Jonathan Cain, the keyboardist and rhythm guitarist for the rock band Journey. Cain alluded to the tragic event in the lyrics of the 1983 Journey song “Ask the Lonely”:

As you search the embers

Think what you’ve had, remember

Hang on, don’t let go now.

In memory of those angels who died 65 years ago, a memorial mass will be held this Sunday, December 3, at Mission Our Lady of the Angels Church. For more information on the services and tragedy, visit olafire.com.

No Comments